- You are here:

- Home »

- Blog »

- Joint Health / Pain »

- Can You Fix Your Shoulder Pain By Hanging From a Bar?

Can You Fix Your Shoulder Pain By Hanging From a Bar?

Rule of thumb: if you hear that there’s just one thing you can do to fix a physical ailment, like those annoying web page ads that read “Fix XYZ using this one weird trick!”, red flags should almost block your field of view.

The more you learn and know about a particular problem, the more you realize the nuance involved in solving it.

Back in the 80’s, the way to solve lower back pain was by using the McKenzie Method. And although the method is more complex than just one thing, it got reduced to “extension exercises”. Did it help people? Yes but not past about 30 days of back pain which is actually not remarkable since the natural history of back pain tends to improve over the first 30 days anyway.

Now, for shoulder pain, the new “one thing” is hanging from a bar.

Basically, you suspend yourself in the starting position of a pull-up, hold that position until you can’t and keep doing it preferably several times a day (this is a key point so remember this one) up to 15 minutes of hanging time.

That’s it or that’s what it gets reduced to on the Internet.

And there’s plenty of anecdotal evidence that it works at least for some people.

The concept started with an orthopedic surgeon – Dr. John M. Kirsch – who wrote a book on the subject which has gained a lot of traction, positive reviews, and remarks.

Dr. Kirsch’s theory is that due to the lack of overhead use in everyday life, a certain part of shoulder anatomy gets too tight, atrophies, and then interferes with shoulder movement.

Of course, you don’t have to understand the theory to use the concept. You could just quit reading this, buy the book, and roll the dice. Might work just fine.

But many of my readers are interested in understanding how or why something works.

So, let’s explore.

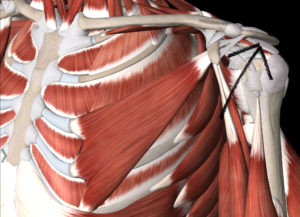

The structure Dr. Kirsch refers to is a ligament- the coroacromial ligament – which is part of an area in the shoulder called the subacromial space.

And a common problem with this space is that the tissues that lie under it get pinched or squished as you move your arm around mostly above a 90-degree angle of the shoulder. Enough squishing and you can end up with something called Impingement Syndrome.

The thing is, because this space is so tight, you squish those tissues all the time with just everyday movements. The difference between Impingement Syndrome and being pain-free is that your tissues are irritated much like having a splinter in your finger. Ever notice how little pressure it takes to ignite pain from a splinter?

A medical approach to solving this is to prescribe Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) like Celebrex or Voltaren. If the tissues in the space are inflamed then after about ten days, your shoulder will often feel better.

But, not everyone responds well to NSAIDs and of course, there’s the argument that what you’ve done by taking the NSAIDs is reduce the symptoms while not addressing the underlying cause.

So, why does Impingement Syndrome happen?

One theory is that by sitting and standing in a slightly slumped position your scapula (shoulder blade) moves out of its normal resting position. This makes it difficult to move properly and do its’ job when you lift your arm up over your head. See, when you lift your arm up over your head, your scapula rotates out, up and then back. This motion coupled with the arm motion gives you the greatest freedom of movement and the least squishing in the subacromial space.

Try this. Sit upright, tall. Stay in this position and lift your arm, elbow straight, forward, and up as far as you can. Note the end position and how the motion feels.

Now, slump a bit. Repeat the movement but stay slumped.

Notice anything different?

Most of the time, you can’t move your arm as far up. Might even hurt a bit and almost always feels tight.

Now imagine doing this movement a few hundred times a day when you’re packing up your house to move, playing a game of tennis for the first time in years, or painting a ceiling in your house.

Remember, these tissues are used to getting squished but not getting squished a lot in a relatively short period of time.

Most atraumatic (meaning no injury) problems stem from repetitive motion that dings up the tissue a little bit each time and then all of these little dings accumulate leading to symptoms.

Dr. Kirsch believes you have to reshape the subacromial space and you do this by hanging. Maybe that’s what happens. He has some interesting x-rays in his book and a video on his website that demonstrate how the shoulder moves during hanging from a bar.

But the other thing you’re doing by hanging is altering all of the soft tissues, in particular the thoracic spine, that influences how the scapula is positioned and if you change the position, you influence the squishing factor when you move your arm up over your head.

Finally, the stronger your tissues are (muscle, tendon, fascia), the more your shoulder can tolerate, the better it moves, the less symptomatic you’ll become with repetitive motion. So, in his book, in addition to hanging from a bar, he also suggests exercises to strengthen your shoulder and this might be more important than the hanging but without a controlled trial (which is almost impossible to do in a clinical setting), we won’t know.

I’ve used the hanging idea with clients and for some people, it’s helped. But because the hanging itself hurts, is uncomfortable, it’s a tough thing to do when your shoulder already hurts.

If your shoulder pain is from impingement (and there are a number of different reasons your shoulder could hurt, even in the same places), then hanging from a bar along with strengthening your shoulder might help. You have to be comfortable being uncomfortable though for it to work.

Thanks for reading.

If you like this article, why not share it with a friend? If you’re interested in coaching services, please contact my colleague Laurie Kertz Kelly for a free, 20-minute Strategy Session by, clicking here. To get my Secret Weapon to fight knee, hip & back pain and stiffness, subscribe for free today.

Doug Kelsey has been a physical therapist and human movement expert since 1981. He is formerly Associate Professor and Assistant Dean for Clinical Affairs at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and the author of several books. He has conducted over 250 educational seminars for therapists, trainers, physicians, and the public and has presented lectures at national and international scientific and professional conferences. His professional CV is here.